WHAT'S UP THIS MONTH - MARCH 2023

(Link to What's Up April 2023)

(Link to What's Up February 2023)

THESE PAGES ARE INTENDED TO HELP YOU FIND YOUR WAY AROUND THE SKY

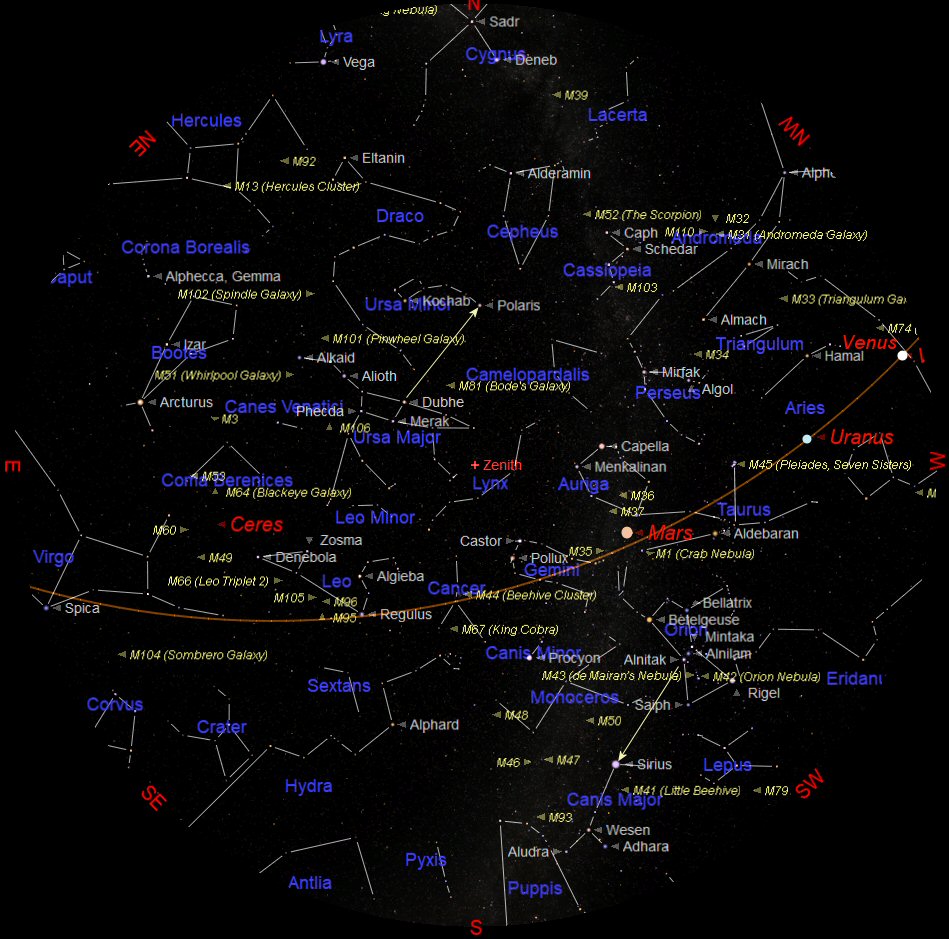

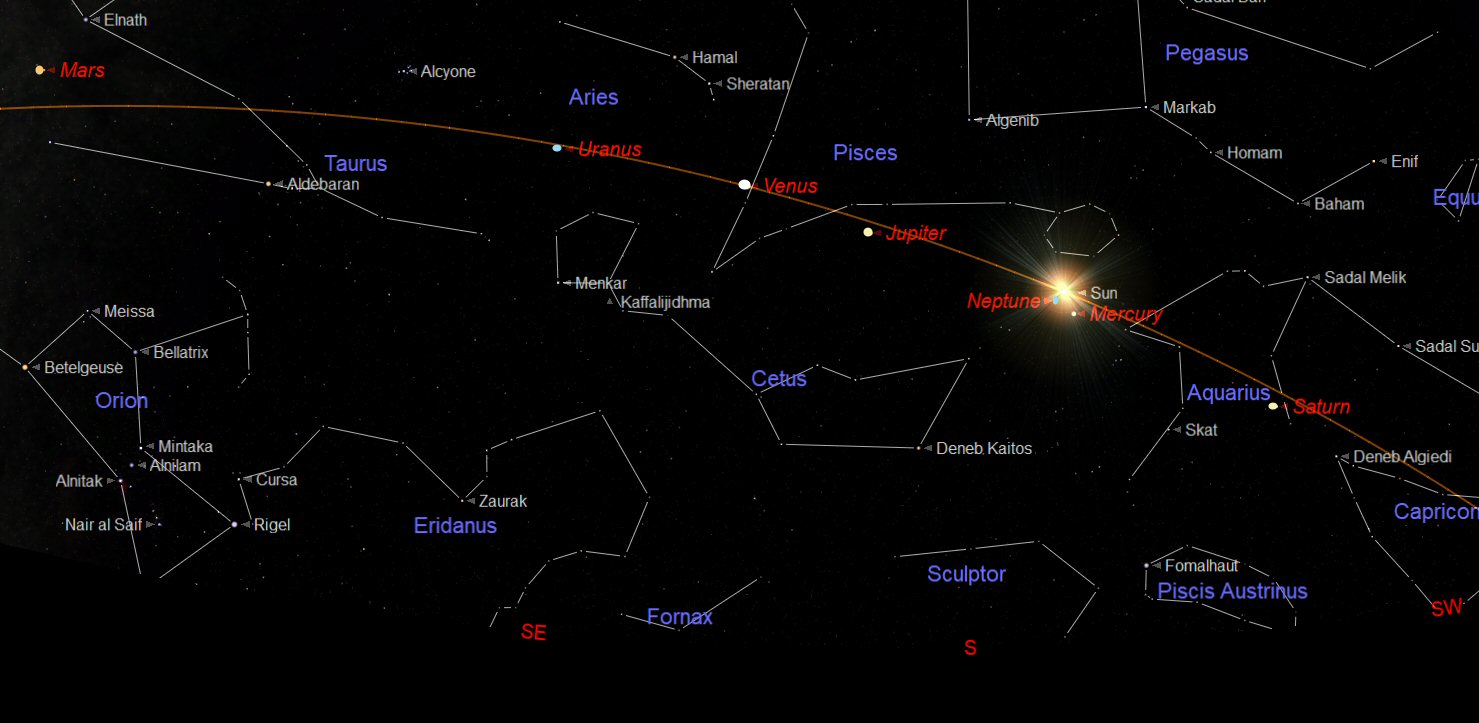

The chart above shows the whole night sky as it appears on 15th March at 21:00 (10 o'clock) Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). As the Earth orbits the Sun and we look out into space each night the stars will appear to have moved across the sky by a small amount. Every month Earth moves one twelfth of its circuit around the Sun, this amounts to 30 degrees each month. There are about 30 days in each month so each night the stars appear to move about 1 degree. The sky will therefore appear the same as shown on the chart above at 9 o'clock GMT at the beginning of the month and at 11 o'clock GMT at the end of the month. The stars also appear to move 15º (360º divided by 24) each hour from east to west, due to the Earth rotating once every 24 hours.

The centre of the chart will be the position in the sky directly overhead, called the Zenith. First we need to find some familiar objects so we can get our bearings. The Pole Star Polaris can be easily found by first finding the familiar shape of the Great Bear ‘Ursa Major' that is also sometimes called the Plough or even the Big Dipper by the Americans. Ursa Major is visible throughout the year from Britain and is always quite easy to find. This month it is almost directly overhead. Look for the distinctive ‘saucepan' shape, four stars forming the bowl and three stars forming the handle. Follow an imaginary line, up from the two stars in the bowl furthest from the handle. These will point the way to Polaris which will be to the north of overhead at about 50º above the northern horizon. Polaris is the only moderately bright star in a fairly empty patch of sky. When you have found Polaris turn completely around and you will be facing south. To use this chart, position yourself looking south and hold the chart above your eyes.

Planets observable in the evening sky: Venus Jupiter, Uranus, Mars and Jupiter in the early evening.

THE SOUTHERN NIGHT SKY THIS MONTH

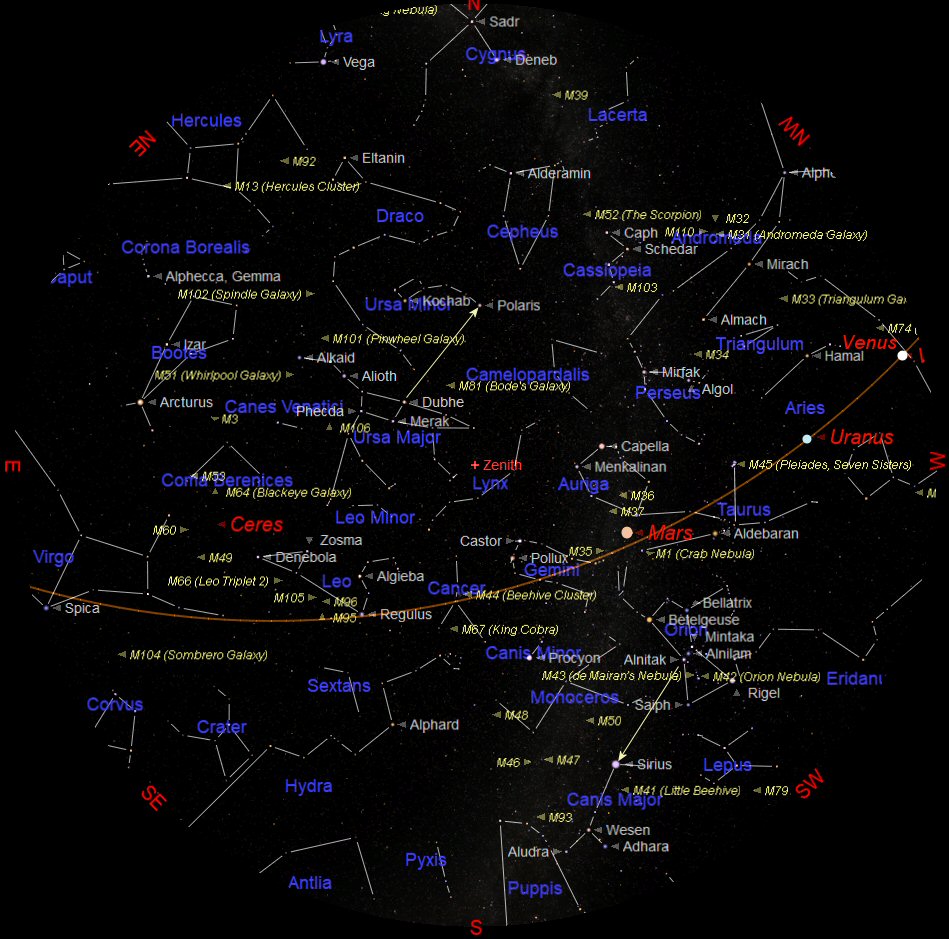

The night sky looking south at about 20:00 GMT on 15th March

The chart above shows the night sky looking south at about 20:00 GMT on 15th March. West is to the right and east to the left. The point in the sky directly overhead is known as the Zenith and is shown (in red) at the upper centre of the chart. The curved brown line across the sky at the bottom is the Ecliptic or Zodiac. This is the imaginary line along which the Sun, Moon and planets appear to move across the sky. The brightest stars often appear to form a group or recognisable pattern; we call these ‘Constellations'.

Constellations through which the ecliptic passes this month are Aquarius (the Water Carrier), Pisces (the Fishes), Aries (the Ram), Taurus (the Bull), Gemini (the Twins), Cancer (the Crab), Leo (the Lion) and Virgo (the Virgin).

Moving over the south western horizon is the constellation of Aries (the Ram). Aries is rather faint and indistinct but it is worth finding this month because the planet Uranus is located within its boundaries. Uranus can just be seen using binoculars but it looks like a slightly blue ‘fuzzy' star using a telescope.

High in the south west is the constellation of Taurus (the Bull). The most obvious star in Taurus is the lovely Red Giant Star called Aldebaran. It appears slightly orange to the ‘naked eye' but it is very obviously orange when seen using binoculars or a telescope. Aldebaran is located at the centre of the ‘flattened' X shape formed by the brightest stars in Taurus. It appears to be in a cluster of stars known as the Hyades but it is not a true member and is much closer to us.

The bright orange planet Mars is in Taurus but is now looking smaller as it moves further away from us. At the end of the top right (upper west) arm of the ‘X' of Taurus is the beautiful ‘naked eye' Open Star Cluster Messier 45 (M45) known as the Pleiades (or the Seven Sisters). It really does look magnificent using binoculars. Just above the star at the end of the lower left arm of the ‘X' is the faint Supernova Remnant Messier 1 (M1) the Crab Nebula. This exploding star was seen as a bright new star in 1054 and can still be seen as a faint patch of light using a medium telescope in a dark and clear sky.

Following Taurus is the constellation of Gemini (the Twins). The two brightest stars in Gemini are Castor and Pollux that are named after mythological twins. To the north of Taurus is the odd pentagon shape of Auriga (the Charioteer). Dominating Auriga is the brilliant white star Capella which is almost directly overhead. For those with a telescope there is a line of lovely open clusters to search out in Taurus and Auriga. These are M35 in Taurus and M36, M37 and M38 in Auriga.

To the east (left) of Gemini is the rather indistinct constellation of Cancer (the Crab). The stars of Cancer are quite faint and can be difficult to discern especially in a light polluted sky. It is really worth searching out Cancer using binoculars or a telescope to see the Open Cluster M44 (the Beehive Cluster). M44 is older and further away than M45 (the Seven Sisters) so is fainter than M45 but still looks lovely. It has a group of stars that resemble an old straw Beehive with bees around it.

To the south of Taurus and Gemini is the spectacular constellation of Orion (the Hunter). Orion is one of the best known constellations and hosts some of the most interesting objects for us amateur astronomers to seek out. Orion was the constellation of the month in January.

The constellation of Leo (the Lion) follows Cancer along the Ecliptic and is the constellation of the month this month, see page 9. It does actually look a little like a lion or the Sphinx in Egypt.

WHERE TO FIND THE PLANETS THIS MONTH

Mercury will be in Superior Conjunction with the Sun on 17th March and cannot be seen.

Venus will be visible in the early evening sky as soon as possible after sunset. It will be easy to find but it will require a clear view to the western horizon. Venus will gradually appear to increase in diameter as it moves closer to us. However it will also appear as a thinning crescent so the apparent brightness will remain almost the same .

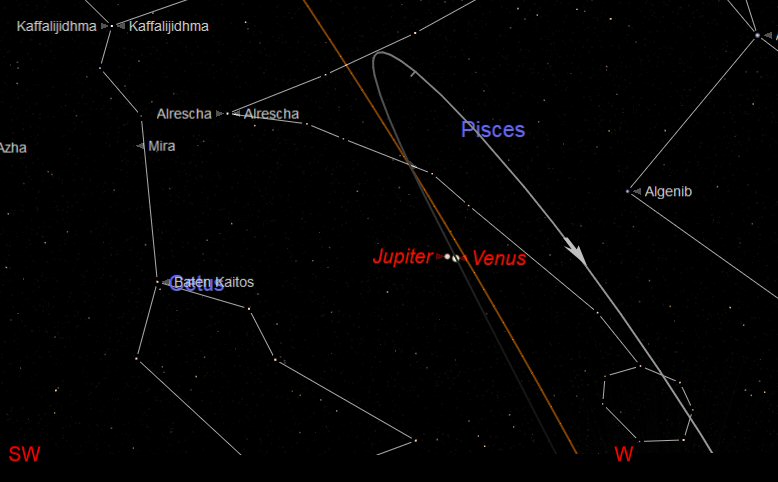

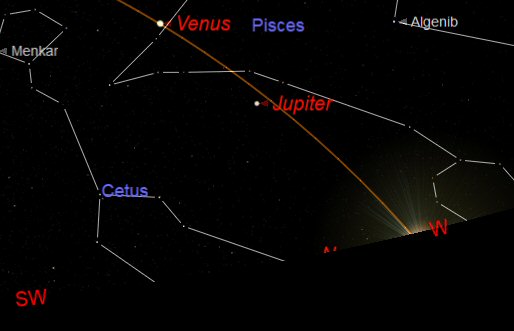

Venus will be in conjunction (very close to) Jupiter in the west on 1st and 2nd March.

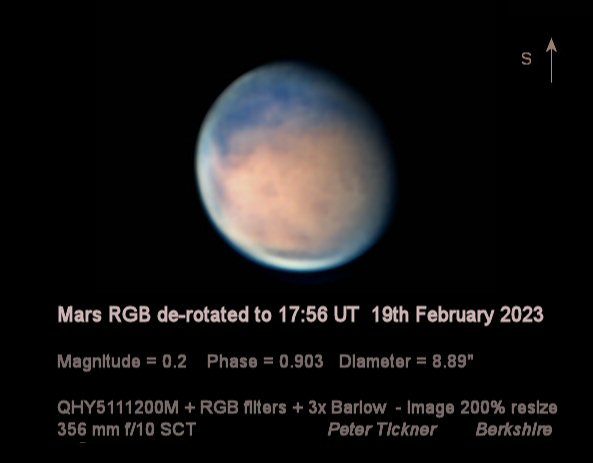

Mars can be seen almost directly overhead as it moves from Taurus into Gemini at the end of the month. It is starting to look small at about 7" (arc-seconds) as it moves further away from us. So Mars is past its best and is now starting to fall behind Earth and will appear to be getting smaller and fainter as it moves away from us.

Jupiter is bright just observable over the south western horizon in the early evening. The cloud markings can be seen and the four brightest moons will be visible in binoculars or a small telescope. It will be very close to the brilliant Venus at the very beginning of March.

Saturn will be moving out from its conjunction with the Sun and will emerge into the early morning sky but will be too close to the Sun for observing.

Uranus will have a close encounter with Venus on 30th and 31st March so it will be a good time to look for Uranus.

Neptune is will be in conjunction with the Sun on 16th March so will not be visible.

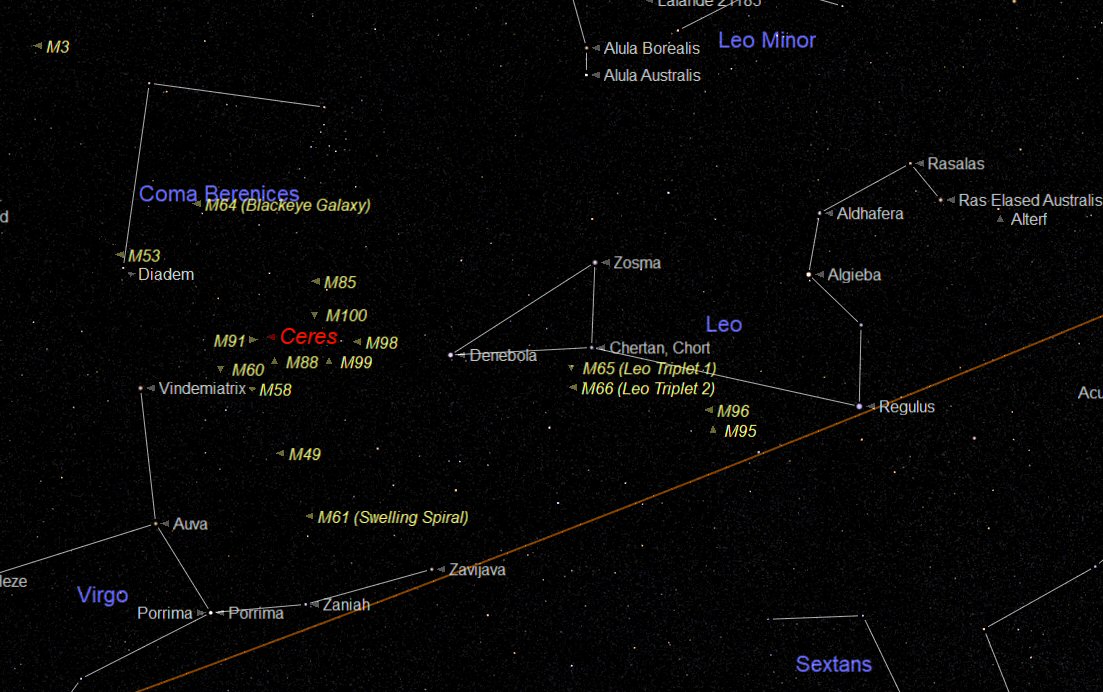

GALAXIES IN LEO, VIRGO AND COMA BERENICES

Galaxies in the constellations of Leo, Virgo and Coma Berenices

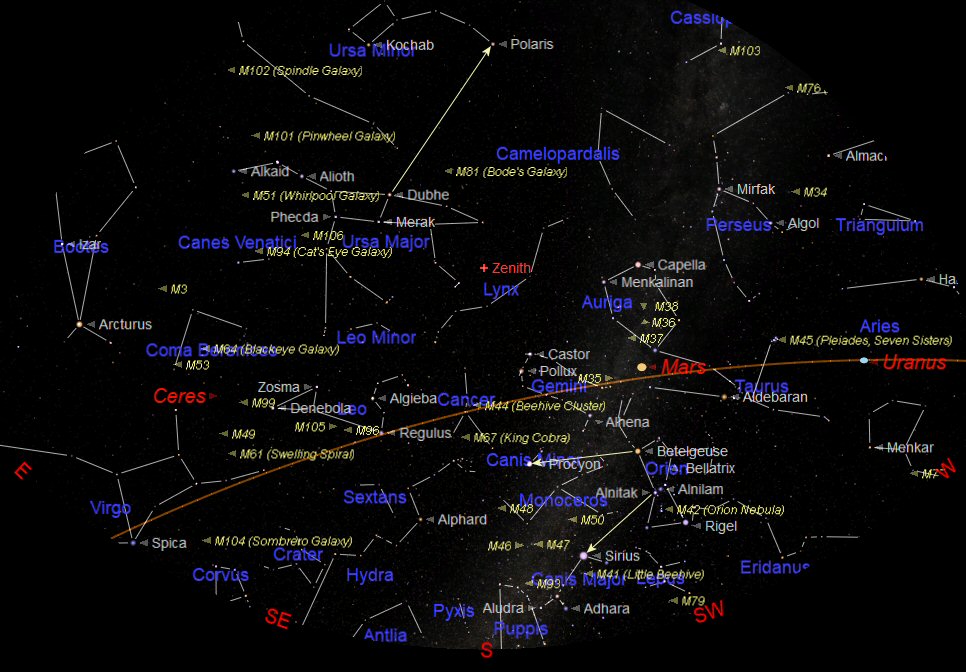

Spring time is often regarded as the season of galaxies. Th is is because there is a group of Galaxies located between the constellations of Virgo , Coma Berenices and Leo. In the chart above Leo ha s f our lovely bright (Messier) galaxies of its own, these are known as: M65, M66, M95 and M96. They can be seen on the chart above marked in yellow just below the shape of Leo the ‘lion'. Now is the time to search for the galaxies before the spring night sky brightens.

Leo is quite distinctive with the ‘S ickle ' shaped pattern of stars looking much like the head of the lion that Leo represents. In fact the traditional ‘stick figure' shape of Leo as shown on the chart above does look rather like the lion's body or the Sphinx in Egypt. The ‘ S ickle' is also described as looking like a backwards question mark (?).

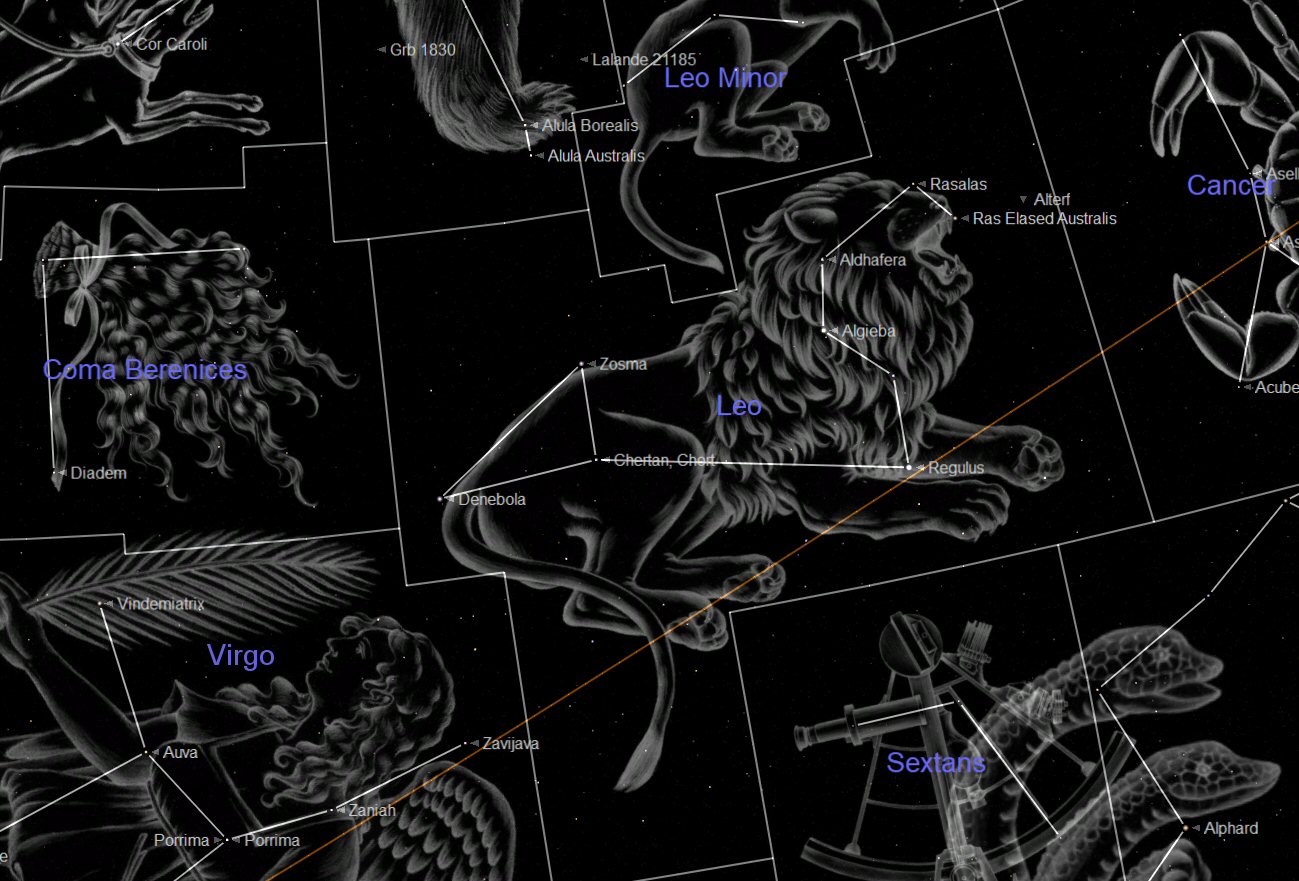

A classical illustration of Leo (the Lion) with constellation boundaries

Leo does look unexpectedly large in the sky and may be a little difficult to find for the first time but once found it is easy to recognise and find again .

Regulus (located at the base of the sickle) is a large blue / white star approximately 160 times brighter than our Sun and lying at a distance of 69 light years. When viewed through a small telescope a smaller companion star can be seen close by making Regulus a double star. Regulus sits virtually on the ecliptic line (the brown line shown on the chart above) . This is the imaginary line along which the Sun, Moon and planets appear to move across the sky. Leo is therefore one of the twelve constellation s of the Zodiac.

Every eighteen years Regulus is ‘occulted' by the Moon so every month for a period of eighteen months the Moon passes in front of Regulus. An occultation occurs when the Moon passes in front of the star so the star disappears behind the Moon. The last series of occultations occurred around 2007 and the next series will be around 2024. The Moon does however pass close to Regulus every month. It will pass close but above Regulus on the 28th March at 13:00 but the event will not be observable from the UK.

The star Algieba, located above Regulus on the ‘Sickle', is a very nice double star about 75 light years from us. The two stars orbit each other around their common centre of gravity every 620 years and have magnitudes of +2.2 and +3.5 which give them a combined magnitude of +1.98.

When we look in the direction of Virgo we are looking up and out of our Galaxy (the Milky Way). We are not looking through the main disc structure so our view it not obscured by the multitude of stars and thick clouds of gas and dust in our galaxy. With this clearer view out of the Milky Way we are able to see the other galaxies that surround our galaxy. Some of the brighter of these local galaxies are called the ‘Virgo Cluster' and marked in yellow on the chart above.

Virgo is located on the ecliptic ( the imaginary line along which the Sun, Moon and planets appear to move across the sky ). This means the Sun, Moon and planets can appear to pass through Virgo . Virgo is one of the ‘Spring Constellations' because it enters the night sky in the early months of the year as it begins to rise over the eastern horizon in the evening. Most of its stars are not bright but Spica is the exception. It is a variable star with an apparent brightness (known as magnitude) that varies between +0.97 and -1.4. It is classified as the 16 th brightest star in the night sky.

Spica is listed as a Spectroscopic Binary star. This means it is a double star but the two stars are so close together that they cannot be separated using a telescope. It was found to be a double star when the spectrum of the star's light was found to be the combined spectra of two different stars. The pair is so close together that the gravity has caused them to be elliptical (egg shaped) as the part of each star facing the other is pulled towards the other by their gravity.

The two Spica stars are both larger and hotter than our sun but are only 18 million kilometr e s apart. That is very close for stars. For comparison, Earth's distance from our S un is 150 million kilometr e s. They are so close to each other that t heir mutual gravity distorts the star s to produce a bulge pulled towards the other as they whirl around . They orbit around each other and their common centre of gravity in just four days.

An artist's impression of the Spica pair

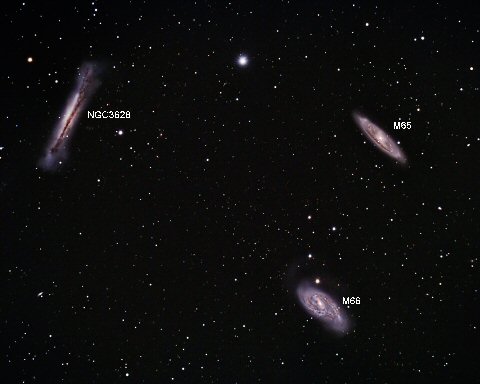

The galaxies on the previous chart are shown in detail below. A 100mm to 150mm aperture telescope will be required to see the faint ‘misty' outline of these galaxies. There is a third galaxy close to M65 and M66 called NGC3628 these three are known as the Leo Triplet.

The Leo Triplet M65, M66 and NGC 3628

Messier 66 (also known as NGC 3627 ) is a barred spiral galaxy that is about 36 million light-years away in the constellation Leo. M66 has an apparent magnitude of +8.9. It was discovered by Charles Messier in 1780. M66 is about 95 thousand light-years across with striking dust lanes and bright star clusters along sweeping spiral arms.

M66 showing the Spiral Arms at the end of a bar

Messier 65 (also known as NGC 3623 ) is a spiral galaxy that is about 35 million light-years away in the constellation Leo. We see it slightly tilted away from us. It was also discovered by Charles Messier in 1780.

M65 showing a dust lane in the Spiral Arms

There is another beautiful pair of galaxies called M95 and M96 further to the west (right) of M65 and M66 below Leo that can also be seen using a small telescope on a clear dark night.

Galaxies M96 and M95 in Leo

Messier 96 (also known as M96 or NGC 3368 ) is a spiral galaxy that is about 31 million light-years away in the constellation Leo. M95 and M96 were discovered by Pierre Méchain in 1781 and catalogued by Charles Messier four days later.

M96 has a deformed arm (top)

Messier 95 (also known as M95 or NGC 3351 ) is a barred spiral galaxy that is about 38 million light-years away in the constellation Leo.

M95 is seen almost ‘face on' to us

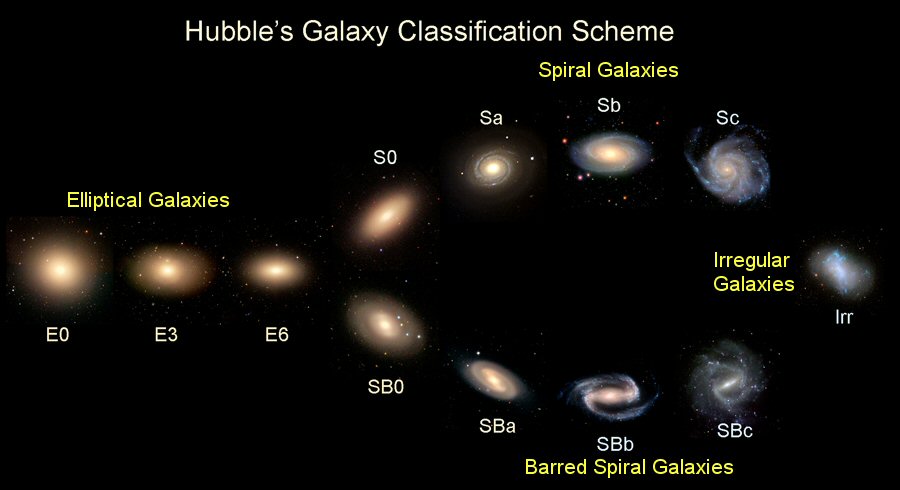

Galaxies are classified into four types, these are: Elliptical, Spiral, Barred Spiral, and Irregular. Elliptical galaxies are generally the largest and Irregulars the smallest. The great American astronomer Edwin Hubble (whom the Hubble Space Telescope is named after) devised a theory about how galaxies formed. The ‘Y' shaped diagram that Hubble produced to demonstrate his theory is still used today to classify galaxies and is shown below.

Edwin Hubble's classification of galaxies diagram

IRREGULAR GALAXIES

These galaxies are , as the name implies , large groups of stars but with no classifiable shape, in other words they may be any shape. Our giant spiral galaxy and the other close giant spiral galaxy known as M31 or t he Great Spiral Galaxy in Andromeda, have smaller irregular galaxies associated with them as satellite galaxies. Two of the irregular galaxies associated with our galaxy can be seen from the southern hemisphere as islands broken off the Milky Way. These are known as the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. These two Irregular Galaxies are gravitationally tied to our Giant Spiral Galaxy (the Milky Way).

The Small and Large Magellanic Clouds

The Large Magellanic Cloud is located 163,000 light years from us and contains about 30 billion stars. The Small Magellanic Cloud is about 200,000 light years from us and contains around 3 billion stars. Both of the Magellanic Clouds have had their shapes distorted by gravitational interactions with the Milky Way. As these galaxies pass near to the Milky Way, their gravitational pull also misshapes the outer arms of our galaxy. The Large Magellanic Cloud contains a highly active ‘starbirth' region called the Tarantula Nebula. These two small galaxies will be inexorably drawn in and cannibalised into our galaxy.

SPIRAL GALAXIES

M any galaxies are disc shaped with spiral arms. Some have arms like curved spokes in a wheel, some gently curved, some tightly wrapped around the central ‘bulge' . The spiral class is preceded by ‘ S' for Spiral and ‘SB' for Spiral Barred. Spiral and Barred Spiral galaxies are further divided into three subdivisions a, b and c depending on how tightly the arms are wound. They are therefore referred to as Sa, Sb and Sc or SBa, SBb and SBc. The Great Galaxy in Andromeda M31 is our closest giant spiral neighbour and can be seen using binoculars and even be seen with the naked eye on a very clear night and from a dark location.

Messier 31 (M31) the Great Spiral Galaxy in Andromeda

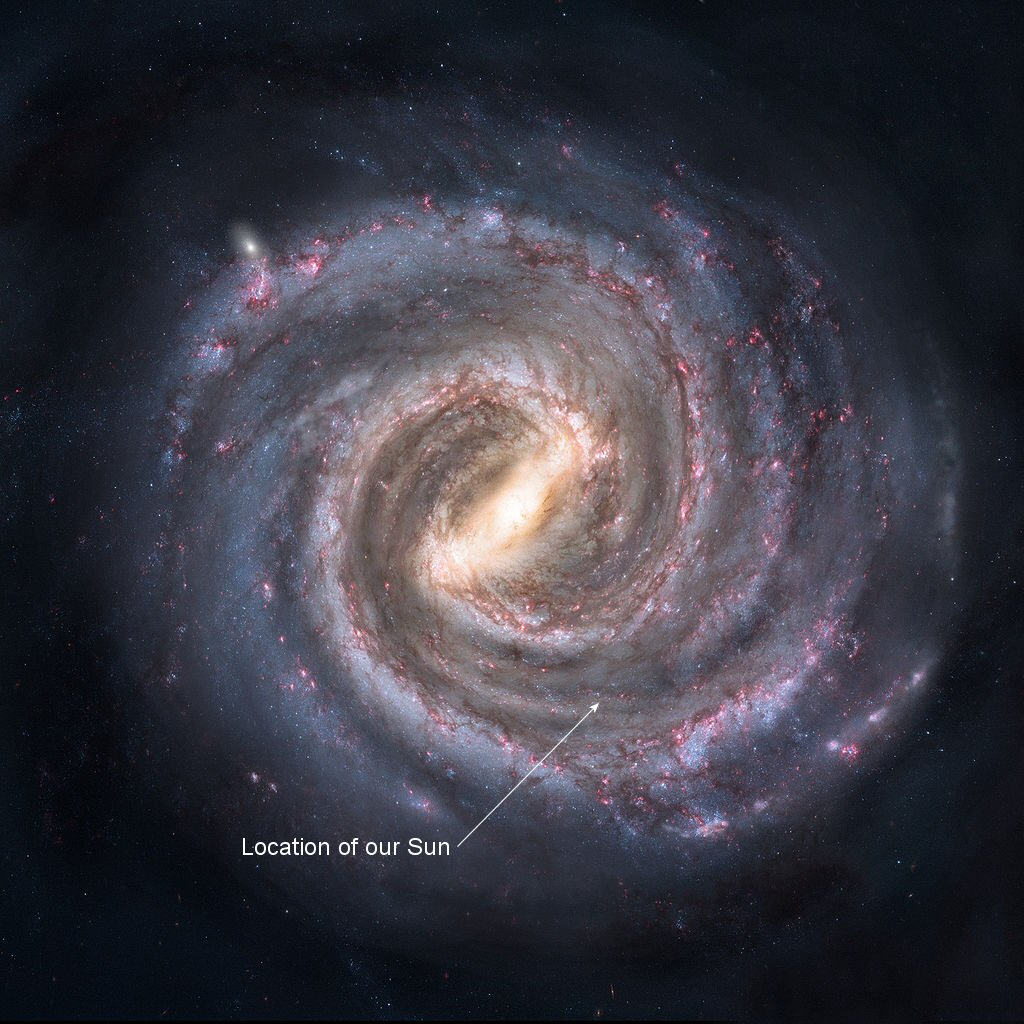

Spiral Galaxies generally have star formation in the spiral arms and this can be seen as blue and pink colours in the arms of our galaxy in the image on the next page. Spiral galaxies rotate as a solid disc and not faster towards the centre (as would be expected) due to the influence of huge amounts of dark matter they contain. The spiral arms are actually more like shock waves moving through the disc. As the shock wave passes through the disc, gas is compressed and new stars are formed. This new star formation then adds to the shock wave.

Our Milky Way has 200 to 250 billion stars and the Andromeda Galaxy may be up to twice the size probably with more than 400 billion stars. All the other members of our ‘Local Group' are smaller with many of them located like satellites around the two giant spiral galaxies.

There are other smaller spiral galaxies such as M33 shown below. Messier 33 (M33) is a smaller Spiral Galaxy also known as the Triangulum Galaxy. M33 is approximately 3 million light-years from us and is located in the constellation Triangulum. It is catalogued as M33 or NGC 598, and is sometimes informally referred to as the Pinwheel Galaxy . It appears ‘face on' to us and is thought to contain up to 40 billion stars. It also has a lot of star forming activity.

Messier 33 (M33) a smaller Spiral Galaxy

BARRED SPIRAL GALAXIES

Some Spiral Galaxies have what looks like a straight bar of stars extending out from the central b ulge. Our galaxy (the Milky Way) is now thought to be a Giant Barred Spiral Galaxy. T he spiral arms are attached to ends of the bar so these are called Barred Spiral Galaxies. It was originally thought that the ‘Bar' naturally formed as normal spiral galaxies matured but they are now thought more likely to be created by gravitational forces.

An artist's impression of how our Milky Way Galaxy may appear

ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES

These are huge balls of stars that do not have spiral arms and are elliptical (egg shaped). Many of these Elliptical Galaxies are the largest of all star groups with some having thousands of billions (trillions) of stars. Elliptical Galaxies are classified according to how flattened they appear , nearly round ones are known as E0 and sausage shaped ones E7. Most Elliptical Galaxies are far away and therefore appear very faint and need a telescope to see them.

Messier 87 (M87) a Giant Elliptical Galaxy

There are many indications that the giant elliptical galaxies grew from the collision of two or more smaller galaxies. There are indeed some galaxies which can be seen to be in the process of colliding and combining. Messier 87 is the biggest galaxy in our immediate area of the universe. It is thought to contain around 2.7 trillion stars and dominates our ‘Local Group'.

THE SOLAR SYSTEM – MARCH 2023

The location of all the planets at midday on 15th March

The chart above shows the location of the planets along the Ecliptic. The planets except Saturn, Mercury and Neptune will be visible soon after evening at sunset. Saturn is now in the early morning sky before sunrise. Mercury and Neptune are in conjunction with the Sun and Saturn rises before the Sun in the early morning sky but will be very difficult to see.

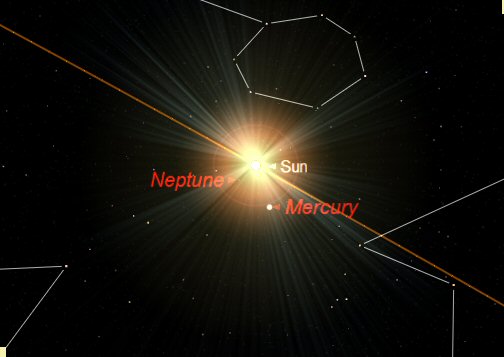

MERCURY will be in Superior Conjunction with the Sun (located on the far side of the Sun) on 17th March and cannot be seen.

Mercury and Neptune in conjunction with the Sun during March

VENUS will be visible in the south west as the Sun is setting over the horizon. It is very bright and will be easy to find but it will require a clear view to the western horizon. Venus will gradually appear to increase in diameter as it moves closer to us. However it will also appear as a thinning crescent so the apparent brightness will remain almost the same.

A telescope is needed to see Venus as a disc and the larger the telescope the bigger Venus will appear. Venus often appears low in sky and in the murky and turbulent air close to horizon. It is best to start with a low power eyepiece (25mm) when observing Venus then use a higher power (magnification) eyepiece (10mm) to have a closer look. The image will probably be too bright so a Moon filter can be used (an adjustable Polaroid type is best). Alternatively the Dust cap can be fitted to the telescope and the small ‘Moon' cap removed to reduce the glare.

If the image looks good then a Barlow Lens can be used to effectively double the magnification of the 10mm eyepiece. When Venus is low in the sky and we are looking through more of our atmosphere so some colour distortion will be seen as red and blue fringes.

The main interest for amateur astronomers when observing Venus is to follow the progress of the phases. The two inner planets Mercury and Venus (known as Inferior Planets) are the only planets to show phases. Phases occur when these planets (and our Moon) are partially illuminated by the Sun. The phases change as the planets move around the Sun on their orbits. Venus will be very close to Jupiter on 1st and 2nd March, see the chart below.

The orbit of Venus shown brighter on the future path back towards the Sun

MARS can be seen high in the evening sky as soon as the Sun has set and the sky darkens. It is looking small at about 7.5" (arc-seconds). Earth overtook Mars on the inside on 8th December. So Mars is past its best and is now starting to fall behind Earth and will appear to be getting smaller as it moves away from us.

Mars imaged by Peter Tickner from Reading Astronomical Society

JUPITER is past its best for this year but is still good for observing in the early evening. Jupiter was at its very best when it was at opposition on 26th September. At this time it was due south at midnight 01:00 BST and appearing at its highest above the southern horizon.

Jupiter is now moving towards the western horizon during the early evening. It will begin to set over the horizon at 20:00 GMT at the beginning of this month and set by 19:30 GMT at the end of the month. In reality it will start to appear unsteady up to an hour before these times due to the turbulent and muggy air closer to the horizon.

However it is still very worthwhile to observe the King of the Planets in the very early evening for another month or so. The moons are still easy to follow and can be very interesting to see as they move around the planet. A planetarium application will show the positions of the moons and the times of a transit or occultation.

Jupiter after sunset in the west

The movement of Jupiter's moons can be predicted by using a Planetarium Application on a computer. The free to download application called Stellarium is very good for doing this. We are able to predict when a moon will pass in front (transit) or behind the planet (occultation). There is an interesting close approach between Jupiter and Venus on 1 st and 2 nd March. This will provide a good opportunity to take pictures of the conjunction (even with a mobile phone). See the Venus chart.

SATURN is emerging from conjunction with the Sun this month will be moving out from its conjunction with the Sun and will be too close to the Sun for observing. See the chart below.

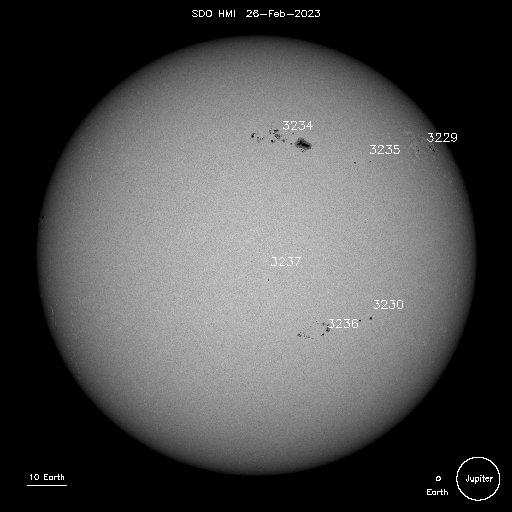

Saturn rising before sunrise in the east

URANUS was at Opposition on 9 th November so was at its best position for observing this year. As Earth overtook Uranus on the inside Earth, Uranus and the Sun were aligned with Earth between the Sun and Uranus on the outside. Uranus is now past its best but is still well positioned from early evening until 23:00 when it will set over the western horizon. See the Venus chart above. It appears as a fairly bright but ‘fuzzy' star when viewed using binoculars but can be seen as a small blue disc when using a telescope.

NEPTUNE will not be visible this month as it will be moving into conjunction with the Sun on 11th March. It will reappear in the bright morning sky after conjunction, see the Mercury chart.

THE SUN

The Sun rises at about 06:40 at the beginning of the month and 05:50 by the end. It sets at 17:50 at the beginning of the month and 18:30 at the end of the month.

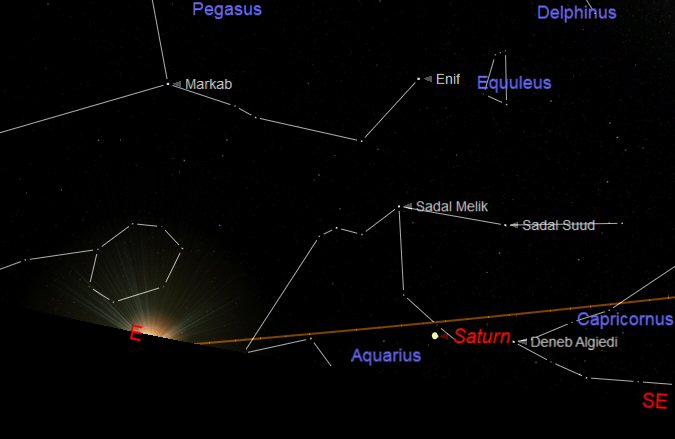

The Sun is over half way through its Active Phase when there is more activity on the surface. There is an 11 year cycle when the Sun increases and decreases activity on the surface. The most obvious change on the Sun is the appearance of Sunspots as shown on the image below. These and other activity is caused by the interaction of powerful magnetic fields in the Sun.

More sunspots appear and there are often huge ejections of energetic particles thrown into space. When these particles encounter the Magnetic fields surrounding Earth they are captured and drawn into the north and south poles. The energetic particles cause the upper atmosphere to glow and produce the Aurora Borealis (northern lights) and the Aurora Australis (southern lights). A beautiful Aurora was seen over much of Britain on the nights of 26th and 27th February that may have been attributed to activity 3234 shown in the image below.

Nearly all telescopes can be modified to allow the safe observation of the surface features on the Sun by fitting a special Solar Filter to the telescope. These filters reject most of the sunlight and only allow a small fraction of the light to pass through. These must be the correct approved type or permanent eye damage can occur. If a telescope is not available the Sun can still be observed by downloading daily images from NASA's orbiting Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) at: http://sohowww.nascom.nasa.gov/ .

Sunspots imaged by SOHO on 26th February

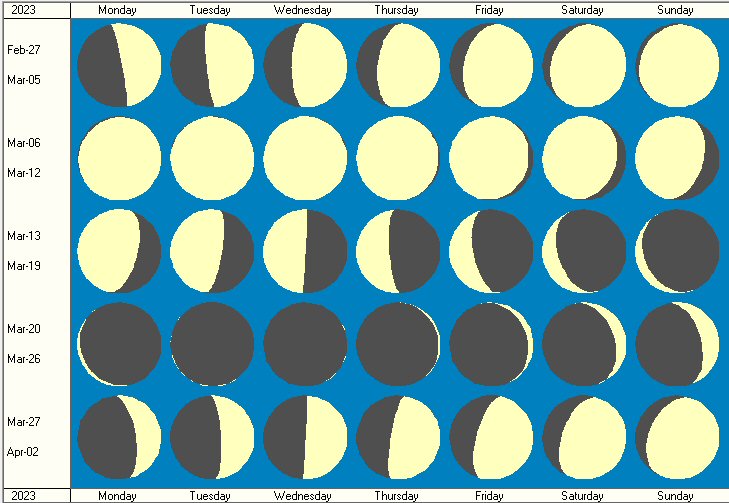

THE MOON PHASES DURING MARCH

Full Moon will be on 5th March

Last Quarter will be on 15th March

New Moon will be on 21st March

First Quarter will be on 29th March